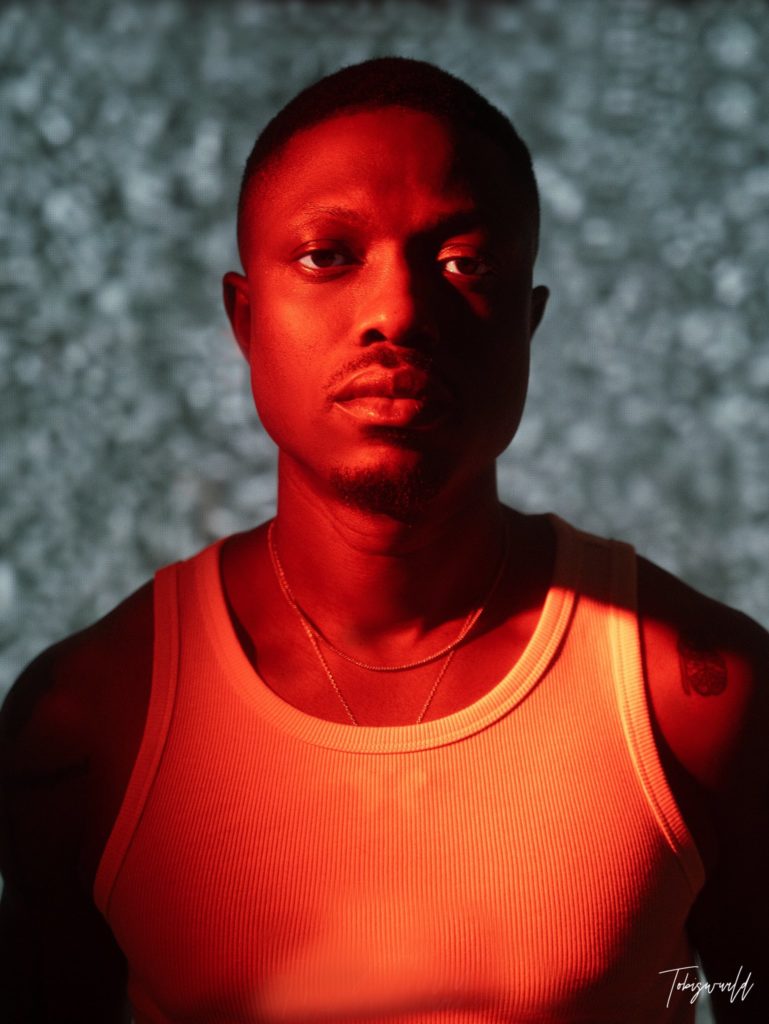

For nearly two decades, Vector tha Viper has rapped each verse like he’s brightening a dull room, transferring his wit and coolness before charmingly bursting into a thousand volts of energy at the song’s end.

Whether subbing record labels that pressure him to spit in “vernacular” (as he called Yoruba in his song “Kilode”) to sell, or boasting about being a better version of what everyone assumes is the best, there’s a self-consciousness and intentional energy to Vector’s rap style that sets him apart. From Sarkodie to Reminisce, M.I Abaga, Jesse Jagz, Show Dem Camp, and many more, Vector has consistently held his place as one of West Africa’s finest.

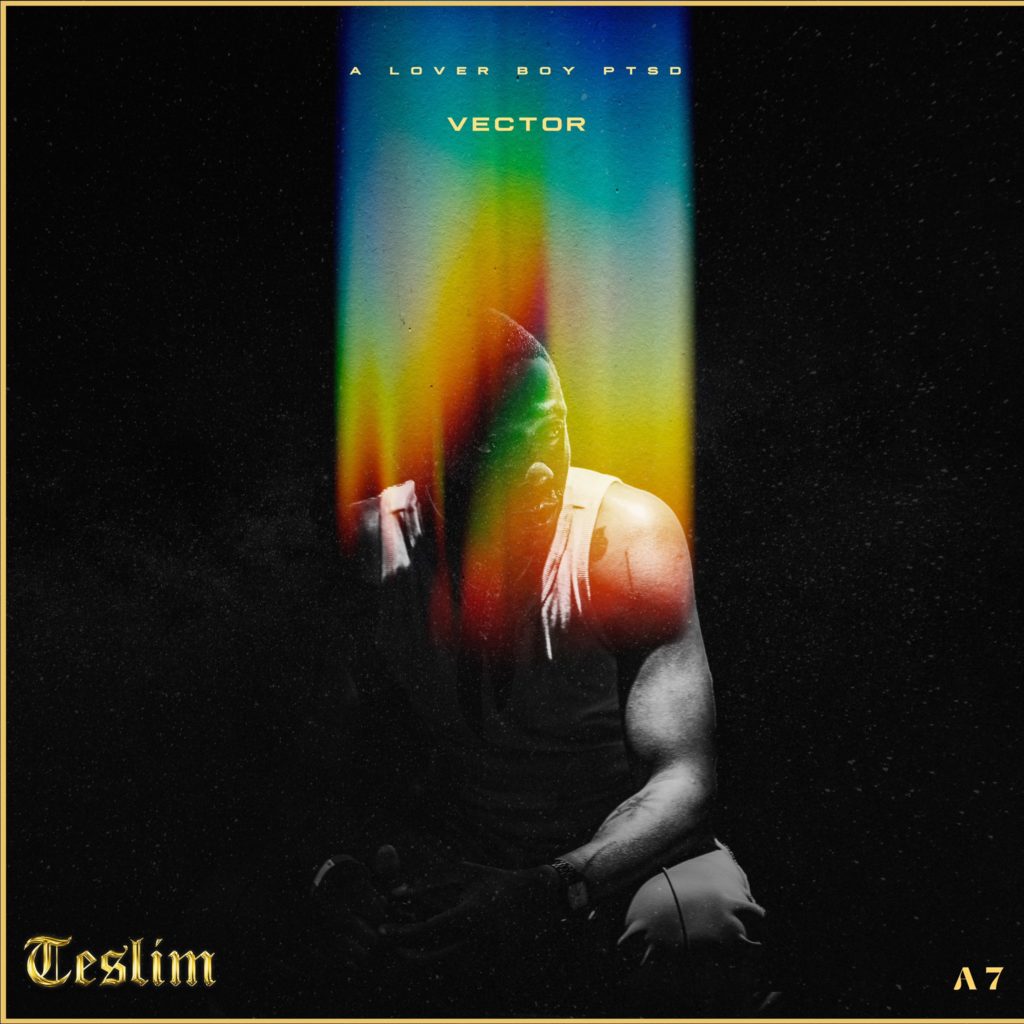

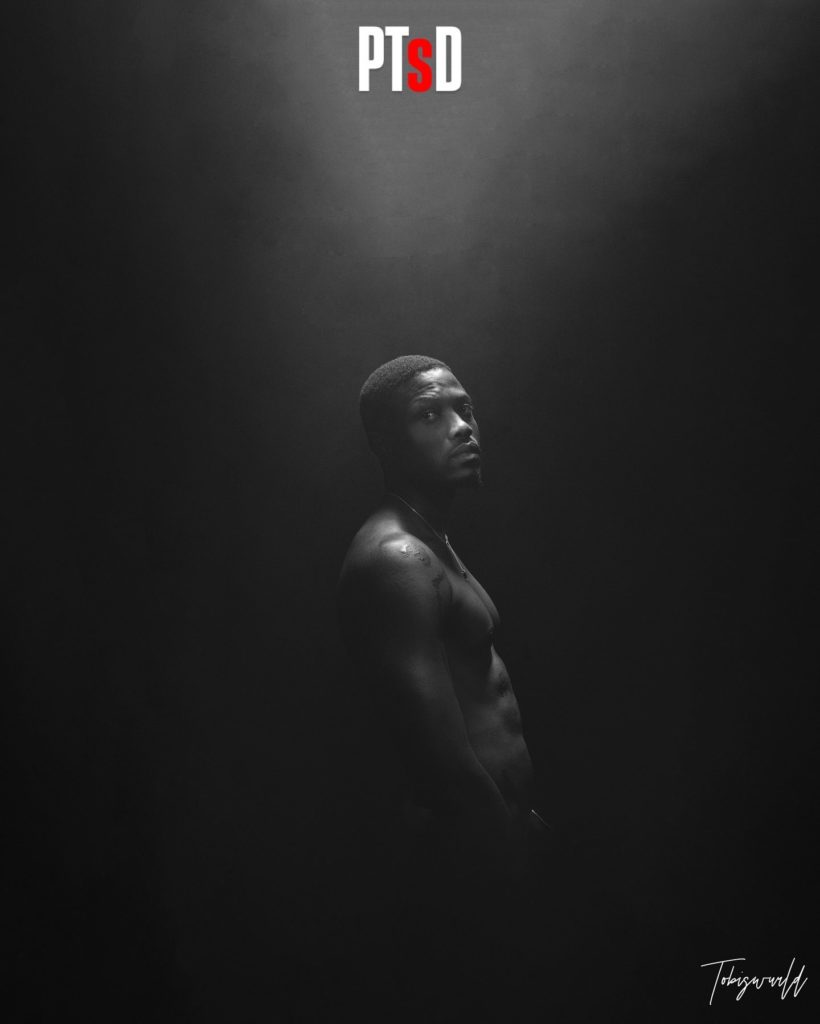

At this point in his career, Vector could focus solely on his mid-range medleys, expressing how he feels, and his legacy would remain intact. On his sixth studio album, Teslim: A Lover Boy PTSD, the Lafiaji rapper embraces his transition into a lover boy. Following the evolution of his “Teslim” persona and earlier instalments in his discography, this new album extensively explores his romantic and experimental sides.

What is the inspiration for this album?

“A Lover Boy’s PTSD” is how the average man would claim they feel about expressing love. Though it’s not just referring to the men: it’s both sexes. But because I’m male and my pronouns are he and him, it had to be a lover stating the fact that he’s a lover boy. The PTSD is the reason why he can’t really show it too much. So, this album is dedicated to the women getting a little good out of lover boys’ PTSD.

You sing a lot in this album, which reminds me of “Early Momo,” as opposed to rapping. Why?

I wasn’t trying to put a certain targeted sound together just to achieve something. I was just making music, and it all came together as such. It’s not something that came from the “Early Momo” wave. As a matter of fact, “Early Momo” rode on a couple of others.

Music can’t be defined whether in creation or after creation, meaning whether in process or success, you still can’t define it. So for what it’s worth, I didn’t make this album targeting any particular thing. It’s just a series of moments where music was made. For example, “Can’t Come Close” is a real life situation happening every other day. The older you get in your journey, the more you have time to maybe address musically some other things that you’ve experienced and one for me would be a whole lot of women.

Knowing that I’ve had many interactions with women and noticing that my pops loved many women, too, I can see how that energy could be transferred.

But this music (singing) is just one of those things that happen as you explore your talent more.

Any fear of giving people what they aren’t used to?

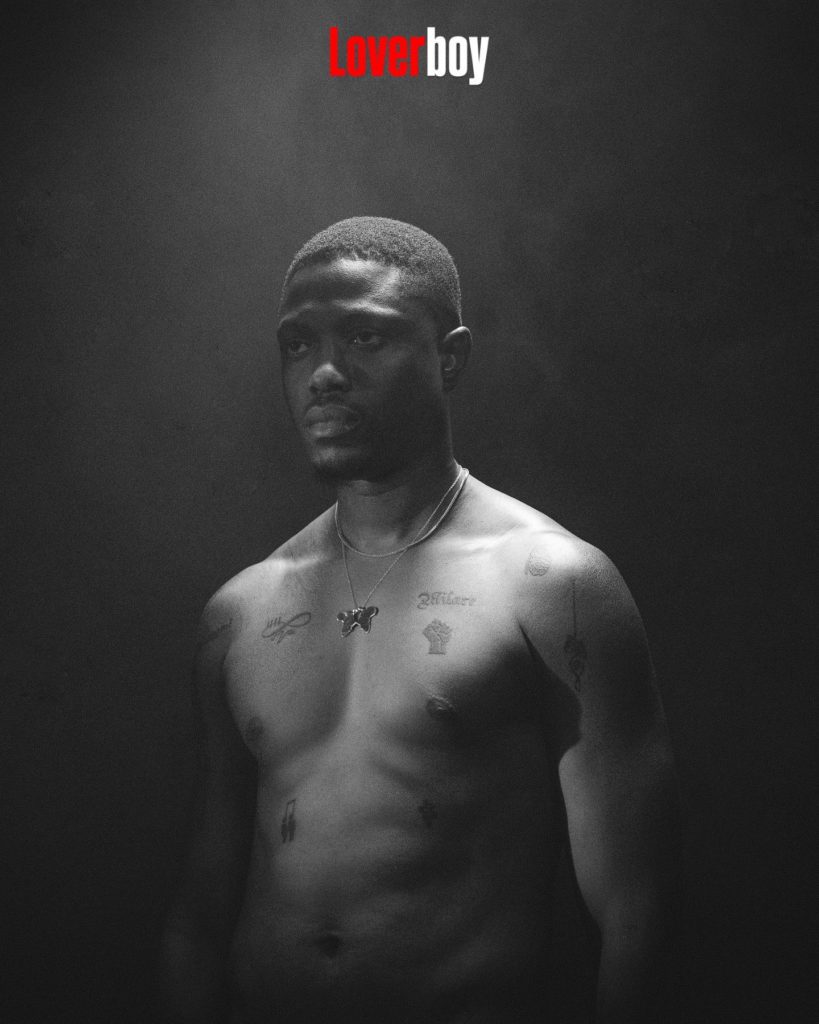

No, never. The only problem I’ve had is people trying to direct my artistry. I’ve always been a mad scientist type of artist, a choir boy.

Yeah, you seem like one, but the rap image has stuck with many people

I know. I’m a rapper, too. It’s both simultaneously well balanced. I’ve never solely made myself a rap image. Probably growing up in the barracks and Lagos Island has shaped how people identify with my artistry, because a lot of rappers build a tough guy persona.

The time people got a lot of raps was its own time. It doesn’t change the fact that I’ve always been a simultaneous artist. I probably may have struggled with it because when I came into the music setting, I often heard that if you’re a dope rapper and you can also sing, you sound like a sissy. I don’t know what that means, but the older you grow, you realize that, for example, in Africa, if rap is “Rhythm and Poetry,” what then is rhythm? It’s melodies. So, the older I got on my journey with music, I realized that you can be dynamically gifted and express those dynamic gifts. I don’t care whether I’m singing or whether it’s rap time; I’m whooping your ass, AKA “I’m just doing me.”

The album is complimented by more singers. Tell me about the collaborations on the new album

The thing about collaboration is I let the music lead. For example, the record with Bella Shmurda existed before he dropped “Cash App.” Destiny never lies when it comes to talent.

You could tell the energy once it comes to your head. You can tell it’s not just about what’s popping or who is ringing. You can tell the appropriate energy for a record. I always go with energy, and the energy can come from anywhere. With “Iya Nla Nla” featuring Niniola, we had met, and we said we were going to make a record together and we just made it. The record with Tiwa Savage was supposed to be “My Dada” with Emmsong and Top Adlerman, but she ended up on “Repay Your Part.”

My brother Kane facilitated the foreign collaborations. Madame Betty, a longtime friend, introduced us to some artists around the time Kane went to Colombia and met their Vice President to discuss the arts, especially the relationship of Yoruba culture in their regions. That was how collaborators like Jossman and Scridge came into the picture. Kane pulled it off, but it’s all just from relationships that we’ve built in the music industry years over.

So, there was no intention to assemble the Justice League, if you know what I mean. The music just needed to honestly be of interest to the collaborators.

How do you maintain total creativity and ownership in the room?

At some point, you speak to execs or people who intend to run management or do things, and everybody just has the same statement: “If there’s money now, we’ll do this.” I understand the place of money in all these things or in achieving stuff in the world. But what about the artists that don’t have money? Does that mean they will not do anything? So, when I heard that a lot, I was like, “Okay, maybe it’s not a wrong thing. Perhaps it’s just not for me. I’ve played that card before, and I don’t know what the structuring is, but there’s just a lot going on that’s straightforward on paper but not in reality.

I personally don’t know how to dwell in that vicinity, so I removed myself from that conversation about people interfering in the arts process a long time ago. One thing I realised as well is that once an artist does this, they start to see less of the artist in a lot of places. The product from the artist is public consumption, but not the artist, like the art.

There was a time when we were up and coming, you always had to be in the club to show that you’re an artist. I felt that was a bit awkward, but who am I to judge a multitude of people doing the same thing? But at some point, you see that being at the club every time doesn’t do anything for your music other than maybe inspire you to make the same type of club music. That’s not the alpha and omega of artistry. I knew that that wasn’t a thing for me. So, I just kind of left it. I didn’t argue with it. I didn’t fight it. I just left it because it’s not a thing for me.

You were in London for the first time this year. How was that?

It was my first time in London this year. I performed my music to people, it was good. It’s one of my moves to take my music around globally and meet fans. The move is also part of artistic liberation because we’re open to going out there and just creating more opportunities for artists from Africa or Nigeria or anybody close to us.

I’m not saying it was intentionally curated for African nationals. I just wanted to get my tour up and be able to see if it was doable. And since it’s doable, let every other interested person come and get it done with us. But it’s definitely about to be more reaching out to the fans because we’ve built over the years.

In recent times, your music has pointed to the idea of a higher self. Is there a spiritual connection to your music?

It’s just a peaceful expression. To put it in simple terms: I can express more peacefully within the confines of music than I could trying to explain anything to anybody in a conversation. But that’s also a function of spirit, I want to believe that talent is a function of spirit. If that’s so, that means every time talent is being shown, spirituality is happening. Again, spirit lies within. We can’t escape staying in the spirit. It’s also how you tell when an energy is around you. Music has to be one of the most fluid expressions of spirituality.

How do you feel about the idea of legacy? Are you concerned about legacy?

No, I’m not concerned about legacy. You can’t really plan a legacy. Are you trying to tell me that the intention of Equatorial Guinea’s Baltasar Engonga was to be known for his 400 leaked sex tapes?

So, I’m not bothered about legacy because you can’t be bothered about the outcome of something you are busy creating. You’re busy with that and you don’t even know what issue you’d meet on that road. I can’t tell you how to see me now and it’s legacy not by the perception of everybody. For a lot of people, the stories they’ve built about me in their heads are different, and they’d spin these stories in different circles that I would never know.

How do you slow yourself down in this fast world we live in now?

I tell myself, “Calm down. Calm down.” But honestly, the only thing to use to slow down a fast-paced world is self-honesty because with honesty to the self, you tell yourself you’re not as fast as the world, and then you run at your pace. I learned to be brutally honest with myself, and that helped me slow down. For instance, at the passing of my dad, I was brutally honest to myself that I had to embrace death because everybody does it. One lives a better life when one embraces death in everyday thoughts.

Is there anything about yourself, old or new, that you see in the new generation of artists?

Have you heard the amount of people that sample “King Kong”? When I see people trying to recreate what I’ve made or my style, I’m proud. You don’t get angry at the fact that you set the trend. You should actually be glad that you were able to set trends. But at the same time, when I hear something that I want to believe is me musically, I just don’t care about it because who am I to say that person is copying from me? What if it’s something else that inspired them as such?

I’m even proud to see the new generation of rappers who can sing or rap.

What lessons have learnt from working with creatives?

I’ve learned how the Nigerian situation stifles creativity because you can’t just get up and go and create. There are so many factors affecting that. Just accommodating expressions from different creatives isn’t easy. Plus, art must be allowed to be done freely.

But the general idea around where we make art is that things can’t even be freely done. So, how can one achieve the highest point of artistic collaboration? Amenities that make things easy for artists are non-existent. That makes them lose their spark. We’re now forced to this cutthroat mentality of, “You better do it how it’s going to bring money or go that place wey things go work o.”